Words: O. Àbalos / Photograph: Lee Brown | 27 Jun 2019

Brian Robinson & Connor Swift, closing the circle

For decades, professional cyclist Brian Robinson (Mirfield, 1930) was largely unknown among his compatriots. His achievements include being the first Briton to finish the Tour de France and the first to win a Tour stage – both in 1956. But these accomplishments had largely been forgotten until British cycling’s recent renaissance. Now, heroes of the past are being rediscovered and reappraised, providing inspiration to a new generation of cyclists. 88 years of age, the veteran cyclist still retains a clear memory of his pro career and of a 1950’s Yorkshire that was very different from the one experienced by Connor Swift (Thorne, 1995), the current British road racing champion. The two cyclists are separated by 63 years of history: two worlds that came within each other’s orbit over breakfast in a tearoom on the outskirts of Knottingley last March.

“The further north you go, the friendlier the people,” says Brian Robinson at the start of our conversation, to an accompaniment of teaspoons clinking in teacups. The brew, with a dash of milk as local custom requires, is the colour of Yorkshire: strong and intense. The veteran cyclist smiles and looks out at the wooden porch of the Birkin Fisheries Tea Room. Located on Haddlesey Road, it’s a frequent pitstop for cyclists riding through this landscape of plains, lakes and rivers south east of Leeds. In fact, Connor Swift has come by bicycle, clad in the British champion jersey of Madison Genesis, the continental team he’s riding with this season [Editor's note: on May 2019, Connor joined French Arkéa Samsic team]. The owners of the tearoom recognise him immediately, but they’re not sure about Brian. Who is that old man? No offence is taken. Robinson is not famous, and his story was practically unknown before 2006. Any chance to shine a light on his legacy is worth seizing. An event commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of his stage victory in the Tour de France – the first Briton to achieve this – got a great deal of media exposure. Up until then he’d been an unsung pioneer, an outsider in his own time. Swift, on the other hand, is part of a generation of cyclists following the trail blazed by David Millar, Bradley Wiggins, Mark Cavendish, Chris Froome, and Ben Swift – Connor’s cousin – among others. But both men are from Yorkshire, which means they only speak if they’re asked a question. Reticence is typical of northerners they tell me. People are friendly, but economical with their words. They smile.

“Yorkshire has everything really, as far as cycling goes,” says the veteran cyclist. “Here it’s dead flat and good for oldies. And on the other side of Yorkshire, as you know, we’ve got Holme Moss, which is my favourite mountain. It can’t be classed as a mountain in world terms, but in Yorkshire it’s a mountain. Then you go up the Dales. Once you get through Leeds and Bradford, you’re free and the countryside is amazing. And North Yorkshire is fantastic.” Swift concurs: "I agree with Brian. I think everyone from Yorkshire is very proud of where they come from. It’s a fantastic place and I love living here.” What about as a place to train? “It’s good for training too,” says Swift. “It’s different compared to abroad. You go on the roads abroad and they’re fast, they’re smooth. Whereas over here they’re a bit slower, a bit grippier, and a bit harder. You do a 200k day over here – like some stages might be in the Tour de Yorkshire – and come the end of the stage everyone definitely feels it in the legs. You can do a 200k sprint day abroad and it’s pretty easy in the wheels. Over here, it’s not so easy in the wheels. And yeah, there’s punchy climbs. There are no huge, long climbs but the climbs are pretty steep. We don’t really use hairpins over here, so you see a hill and it just goes bang, straight over the top. So yeah, fantastic for training.”

Robinson takes this opportunity to offer a comparison: “Holme Moss is my hill. I haven’t got the record (Bramley Wheelers holds the record with a time of six minutes and three seconds) but I’m only two seconds off. It takes just over six minutes. In France or Italy it’s sixty minutes. That’s the difference we face when we go abroad.” This is Robinson’s way of measuring effort, a far cry from the minicomputers that bicycles have these days. “It was wartime when I started training so you just saw two or three cars up the Dales, and that was the end of the story. But now it’s different, you have to cope with the traffic.” In 2014, Robinson was hit by a car while riding his bike. The accident left him with six broken vertebrae, a fractured collarbone and a punctured lung. These are serious injuries for anyone, let alone a man of 84 as he was then. He hasn’t ridden since.

Swift ponders for a few seconds after I ask him about favourite places to ride. “I like to mix it up. Recently I’ve been chucking it off-road a little bit on the road bike, for a change. But I wouldn’t say any particular road stands out. Just any road that’s in Yorkshire. I live in the flatlands, so I’ve got a bit of riding to do before I head out into the peaks and that. I tend to base my training heading towards Sheffield, and the peaks, and around Haddlesey. I like those climbs around there. And there are some nice roads like… ah, I forgot what I was gonna say then!” He laughs. “There’s plenty of chain gangs that I go on as well. There’s a Tuesday morning chain gang, a Saturday chain gang, pretty well known around this area. And there’re loads of guys I can go out and train with and go on the same roads pretty much week in, week out. It don’t really get boring.”

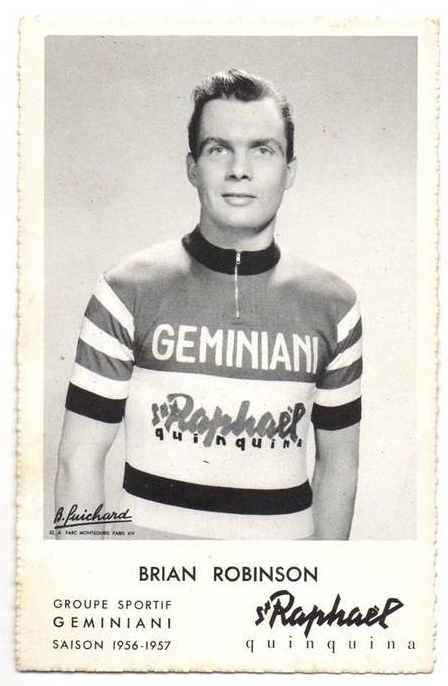

Being able to maintain such a routine with near-religious discipline fits the character of the people around here: stubborn and tough. At least, that’s the stereotype. The famous Yorkshire grit. The routes may be the same, but the Yorkshire weather – so unpredictable – always ensures surprises. “The weather here is not always that great. It can be cold and rainy,” says Swift in his easy, cheerful manner. “The full-time cyclists around here train throughout the winter in quite bad conditions compared to those who live abroad, and that does set you up for the early season races that can be cold. You’ve been training in it, you’ve got used to it. It gives you a bit of that Yorkshire grit if you go out and brave the elements rather than ride on the turbo.” Robinson, on the other hand, talks about this grit as an individual, non-transferable trait. “Each individual has his own personality. It’s a question of being focused. Yorkshire grit is an individual thing, really. I’m sure it’s available in Australia, or any other country. If you’ve got it, you’ve got it, and you’re lucky. I think I had a little bit.” He laughs shyly. Robinson’s story is one of great fortitude and determination. He combined construction work with a professional cycling career. He had to dig deep to catch up to the level of the continental riders after he found a place in French team Sant Raphaël-Géminiani in the 1950s.

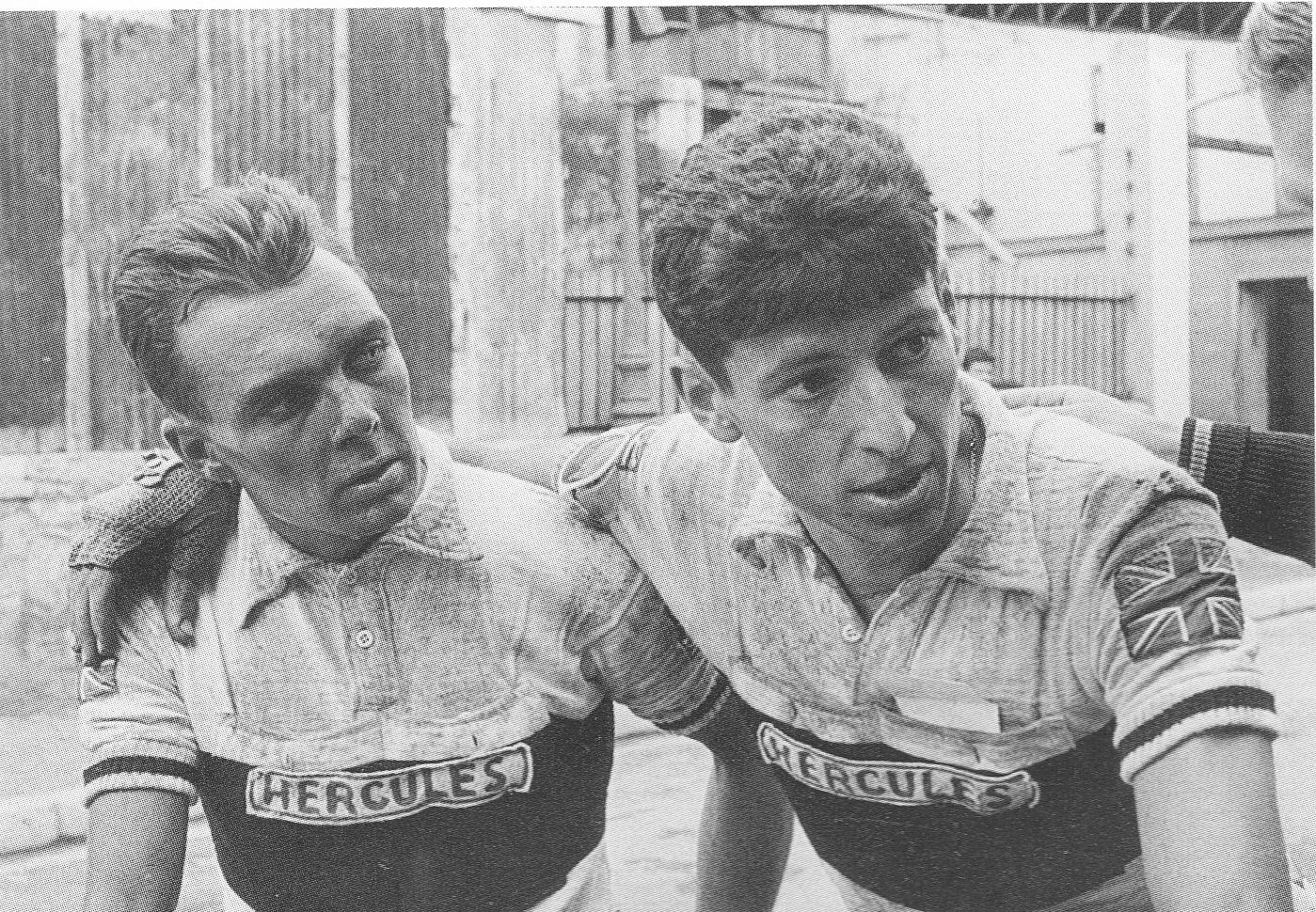

(©Brian Robinson archive)

“The truth is, I never imagined that British cycling would reach the level it has now,” he reflects. “In my time there was no support from anywhere really. You just had to get on with it, as Yorkshire people do.” They both smile. Again, the sense of local pride shines through. “But it’s amazing the progress we’ve made. Going from one lone ranger like me to start with, we’ve now got 50 or 60 guys who can ride the Tour, we’ve got winners of the Tour. So we’ve closed the circle in 50 years. It’s a great achievement. And Yorkshire is now responsible for a large number of cyclists.”

The Vuelta a España and Miquel Poblet

The former pro-cyclist from Mirfield shares some recollections of riding in the 50s while Swift sips tea and listens with interest. “I remember perfectly the first time I climbed mountains in the Pyrenees. It was during a stage of the Tour de France. The race started in Cognac, in the flatlands, and went towards the Pyrenees. They were long stages in those days, so during the first 100k it was very rare that somebody would set the ball rolling. We were pottering along and there was a flash up in the sky, so I managed to say to the guy next to me, ‘Qu'est-ce que c'est ça?’ And he answered: ‘Ce le para-brise.’ They were the windscreens of cars going up the mountain. “‘Are we going up there?’ I asked.” Robinson laughs. “I thought, ‘Blimey, right up there!’ I mean we’re talking what, 3,000 metres, something like that? I think Holme Moss is around 1,700 feet, around 500 metres. So that was a bit of a shock! But I did eventually get up there.”

Robinson also took part in the Vuelta a España. The first one he rode was in 1956. “The first tour of Spain was a bit rough actually, in organization, because it was run by the army, with jeeps. They were the cavalcade if you like. And the soldiers would leave all our luggage on the finish line when we got there and then we had to find our own way to the hotels, which were often seven or eight kilometres away. But you didn’t want to do that when you’ve just done a stage race and you’re all messed up. It wasn’t very good that way. And the food was different from what we ate in France, it was more oily, so you had to be careful about what you ate. But apart from that it was a nice race. It still is a nice race actually.”

During his cycling career he also met riders like Miquel Poblet, with whom he formed a friendship. The Yorkshireman’s face lights up when he talks about the Catalan sprinter. I get the impression that he doesn’t have many opportunities to speak about his experiences in southern Europe. “Poblet was good friends with my team director, Raymond Louviot (from the Raphaël-Géminiani team). Louviot always wanted Poblet in his team, but he didn’t have enough money to compete with Ignis, the Italian team that Poblet was with at that time. So to try and poach Poblet into the Sant Raphaël team, he gave him a bike to ride in the Milan-San Remo. It was 1957. And it was the only time my director asked me to do something. He said, ‘If you’re there at the finish, give Poblet a hand.’ Well, I was there at the finish and I let him out and he won the race of course.” Robinson came third in that race, behind the Belgian Fred de Bruyne. “After that,” recalls Robinson, “Poblet took me to Spain for a fortnight and we had a marvellous time, training and racing and drinking, of course. So yeah, I knew Miquel quite well.”

When Connor Swift, then a Madison Genesis rider, won the men's UK National Road Championships Road Race competition in Northumberland in 2018 (©PA Images)

Swift’s present is lightyears away from Robinson’s past, which we can only see now in black and white photographs. Swift’s career is more closely reflected in other contemporary British riders who have achieved great victories in recent years. “The truth is, having cyclists around you who are capable of winning races like the Tour de France is definitely inspiring. A rider like Simon Yates for example. He used to ride in local circuit races, and now he’s just gone and won the Vuelta a España. It’s pretty crazy. So I think that for a young guy in British cycling, racing the small races, to see that level of success makes it easier to then dream of winning a grand tour or something like that. It’s a pretty exciting time. I’d love to take that step up in the future and ride the Tour, or some of the early season classics, like Flandes and París-Roubaix, that suit someone like me. That’s definitely an aim of mine.”

When cycling visits you at home

At 23, Swift is a cyclist with a great future who’s gradually gaining experience in the higher categories. This year he will defend the British road race championship jersey. “The other day I was looking up the people who have won it on consecutive years. Roger Hammond, who’s the DS this year, won it on consecutive years. John Tanner, a local guy, has won it twice, so it can be done on the trot.” Swift hopes to keep the jersey for another year at least, and would like to wear it in the next edition of the Tour de Yorkshire, from May 2-5. “Riding the Tour de Yorkshire is something really special. In the first few editions I’d go and watch it roadside with my girlfriend and just think of riding it one day. I knew a couple of local guys who were in the race, like Tom Stewart and Graham Riggs – they used to ride for continental teams – and I’d be cheering them on. And obviously I aspired to be on a team like they were. And now I’m here and I’ve done the 2017 and 2018 editions, and potentially the 2019 one in the national stripes. It’ll be pretty special.”

I ask Brian if he wished there had been a race like the Tour de Yorkshire when he was a pro. “It would have been handy. When I started, you couldn’t ride on the road, you rode on an airfield. Or you travelled to Sutton Park in Birmingham, where you started the race at 6 o’clock in the morning, because you had to be out by 9:30 for the park to open to the public. Then we’d ride back home, so it was quite a long weekend.” Six decades later, the UK is immersed in a rich cycling culture that is gaining more and more followers. Robinson has some doubts however. “The arrival of the Tour de France in 2014 did increase the number of cycling fans and people on bikes, but I’m not sure about the quality. I’m an old-fashioned cyclist I suppose, and we were brought up in the club to ride correctly all the time. Now you’ve got a lot of new cyclists who don’t have that experience. They haven’t got the road sense that we were brought up with. It was just natural to us. They have to learn all that beforehand. And some of them are getting quite long in the tooth. People are busy at work and then they retire or take things easier and at 45 they come into cycling. We’re glad to have them, don’t get me wrong, but there is a difference between the old traditional cyclists and the new cyclists.” Swift is a little more positive: “They might not have all the knowledge of riding in a bunch, but I think a lot of the traditional older guys are trying to teach that.”

This 2019, Yorkshire will also host the Road World Championships. This is expected to be a huge event with millions of spectators. “Tom Peacock has a good chance of winning the rainbow stripes in the men’s race,” predicts the man from Thorne. “Yorkshire-wise, there’s my cousin Ben Swift, who could definitely do a ride that day, it’d definitely suit him. And you’ve got Lizzie Deignan in the women’s race. Imagine us taking all the titles. It’d be pretty cool wouldn’t it?" Robinson, the old hand, is more circumspect, though he admits that he’s really looking forward to watching it, talking about it and taking photos. “The World Championship races are always different somehow. You can’t predict what’s going to happen. There’s a large amount of luck, really, in being in the right break at the right time. That’s been my experience of World Championship races.”

The cups of tea are almost empty. Over the last few sips, the two men make some final observations about British cycling. One of them is living it in real time, and his every word conveys the motivation that comes from knowing he’s part of a great moment in his nation’s cycling history. The other observes it all from the perspective of a veteran who’s aware that it hasn’t always been this way. “From my point of view, what’s happening in Yorkshire is unbelievable really,” says Robinson. “Going back a long way, there was nothing like this at all. For a young person that wants to ride a bike and get to the top there’s every facility. The only thing is, it’s a lot harder now because there’s so many want to do it. In my day, you could count on two hands the guys that were capable of riding a national championship. But now it’s so difficult to break into a team. It’s a lot harder than in my day.”

Thanks to Welcome to Yorkshire

* Piece originally published in VOLATA issue #18. Translated into English by Benjamin Palmer.